Exercising in the heat requires extra mental and physical stamina, as well as a different approach to training and nutrition.

In general, there are two kinds of heat: dry heat, in which relative humidity levels are at or below 40%, and humid heat, in which relative humidity levels are above 40% and can reach (rarely) 100%. Your body will respond differently to the heat depending on the temperature and the relative humidity, and it is important to account for this when training or racing in the summer.

Dry Heat:

Dry heat occurs when there is low humidity, which measures water vapor content in the air. Rainfall contributes to humidity levels, so areas with very little rainfall or a desert climate (like St. George, Utah, which hosts the North American U.S. Pro 70.3 Championships) are prone to dry heat.

Often, dry heat does not “feel” as hot as humid heat because the body can more effectively cool itself by sweating. In dry air, not only does the sweat evaporate quickly off the skin, taking extra heat with it, but the moisture from your saliva and breath will also quickly evaporate, resulting in the unpleasant “dry mouth.”

Many endurance athletes report feeling far more thirsty in dry heat than in humid heat for this reason, even though the body tends to sweat more in humid heat at the same temperature.

Humid Heat:

Humid heat results from high temperatures and high levels of moisture in the air. This means sweat does not evaporate as easily, making it harder for the body to cool off. As a result, it can “feel” hotter than the same temperature in a dry environment.

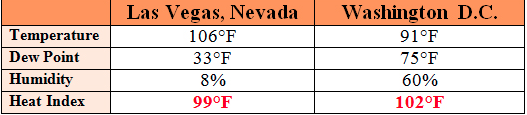

This perceived temperature is known as the heat index, which describes what the temperature feels like to the body when air temperature is combined with relative humidity. As you can see in this chart from the National Weather Service comparing the heat index of Las Vegas, Nevada to that of Washington, D.C., even though Washington, D.C., is 15 degrees cooler than Las Vegas, it feels three degrees hotter due to the humidity.

Ironman Kona, which takes place on the Big Island of Hawaii, is notorious for its high levels of heat and humidity, where 86℉/30℃ can feel like 100℉/37.5℃ due to 80% humidity levels! You can actually calculate the heat index yourself by plugging the air temperature and the relative humidity into this heat index calculator.

To compensate for the sweat not evaporating and cooling the body off, the body sweats more in humid environments:

- A study from the European Journal of Applied Physiology found that sweat rates were higher during exercise in 60% and 80% relative humidity than at 24% relative humidity.

- Not only do people sweat more while exercising in humidity, they sweat more after exercise, as evidenced by this study from Norway. In the study, researchers investigated the relationship between high (85%) and low (19%) relative humidity and sweat rate during inactive recovery after high-intensity work in a hot environment (86°F / 30°C). They found that sweat loss was higher during post-exercise recovery in 85% relative humidity than in 19% relative humidity at the same temperature.

The results underscore the importance of including the effect of relative humidity on both exercise and recovery.

Overheating:

Whether it’s dry heat or humid heat, overheating or heat exhaustion can be dangerous, and can lead to dehydration, fatigue, nausea, dizziness, headaches, elevated heart rate, inability to assess one’s own temperature (due to rise in brain temperature), loss of control of body mechanics, and decline in mental abilities.

When exercising in the cold, symptoms like sluggishness or difficulty maintaining pace can be attributed to fatigue. However, as Runner’s World points out, those same symptoms can mean more than just a lack of fitness or lapse in mental toughness when it’s hot outside.

REMEMBER: Humidity poses a risk to athletes, because as they exercise, the core body temperature rises but the humidity prevents sweat from evaporating efficiently.

Surprisingly, competitive athletes are not immune to suffering from heat-related illnesses; in fact, because they run faster, they generate even more body heat. Factors that may affect one’s ability to handle heat and humidity are body weight, age, acclimatization, and actual sweat content (how much sodium it contains).

If planning to train or race in hot, humid conditions, take precautions. Though race organizers attempt to provide hydration and medical professionals at races in hot climates, sometimes things don’t go as planned. For instance, at the 2007 Chicago Marathon more than 300 people were picked up by ambulances along the course due to heat exhaustion and the event was finally canceled.

According to Runner’s World, “When the race started at 8 a.m., the temperature stood at 72 degrees in the shade, with 83% humidity—many competitors were having trouble keeping themselves cool before the race even started.” The temperature rose throughout the day and over 600 runners and spectators were seen by medical personnel.

Whether you are participating in a medically-supervised race or running a trail on your own, you should follow these tips to keep yourself safe from the heat this summer:

-

Phone a friend: If you’re planning on running for more than an hour in very hot conditions, make sure someone else knows where you’ll be, especially if you plan to run in an isolated area, such as a trail.

-

Ease into it: Early in the summer, your body isn’t fully adapted to running in hot conditions, which means you’ll have a higher-than-normal stress response to the heat. It takes about fourteen days for the body to acclimatize to the heat.

- Pay attention to your body: This is the most important tip. There is a fine line between pushing yourself to greater fitness and pushing too hard. Feeling fatigued and hot is normal. Feeling dizzy, confused, nauseous, or cold (one of the most tell-tale signs of overheating) are not. Slow down and cool down until things return to normal.

What To Do if You Overheat

If you begin to feel the signs of heat stroke, it’s better to stop and accept the fitness gains you’ve made already than to push through and be sidelined for a week or longer.

The Mayo Clinic recommends the following self-treatment for heat exhaustion:

-

Rest in a cool place. Getting into an air-conditioned building is best, but at the very least, find a shady spot or sit in front of a fan. Rest on your back with your legs elevated higher than your heart level.

-

Drink cool fluids. Stick to water or sports drinks. Don't drink any alcoholic beverages, which can contribute to dehydration.

-

Try cooling measures. If possible, take a cool shower, soak in a cool bath, or put towels soaked in cool water on your skin. If you're outdoors and not near shelter, soaking in a cool pond or stream can help bring your temperature down.

- Loosen clothing. Remove any unnecessary clothing and make sure your clothes are lightweight and nonbinding.

In addition to the points above, it is important to make sure that in hot weather you are replacing electrolytes lost through sweat. This is where SaltStick comes in! Supplementing with SaltStick products – Capsules, FastChews or DrinkMix – can help with the effects of dehydration and heat stroke. Please see our usage guidelines to learn how our products can work for you.

Disclaimer: This is for education purposes only and should not be misconstrued as medical advice. Contact your physician before starting any exercise program or if you are taking any medication. Individuals with high blood pressure should also consult their physician prior to taking an electrolyte supplement. Overdose of electrolytes is possible, with symptoms such as vomiting and feeling ill, and care should be taken not to overdose on any electrolyte supplement.